How do Convolutional Neural Networks Work?

Note: Special thanks to Brandon Rohrer from Facebook Data Science for sharing his presentation with us.

Everyone is wondering lately how GANs are able to come up with astonishing images through highly complex neural network. Nine times out of ten, when you hear about deep learning breaking a new technological barrier, Convolutional Neural Networks (CNN) are involved. Now the next obvious question is how do these CNN’s work so efficiently? How CNN’s have learned to sort images into categories even better than humans in some cases?

What’s especially cool about them is that they are easy to understand, at least when you break them down into their basic parts. I’ll walk you through it. There’s also a video buy Brandon Rohrer that talks through these images in greater detail.

X’s and O’s

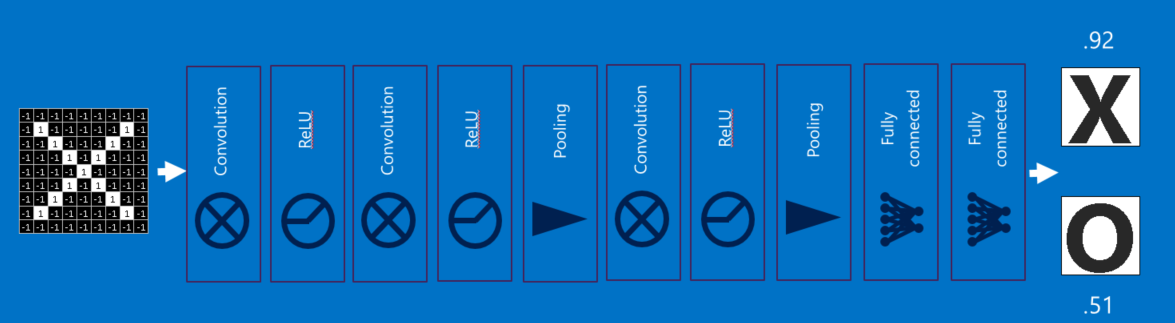

We will start with a very simple example of X’s and O’s in our Convolutional Neural Network walk through. This is perfect example to illustrate the richness of the principles behind Convolutional Nets, but at the same time simple enough to avoid getting bogged down in on-essential details. To illustrate what CNN do, we will start with simple image classification example i.e. given an image, CNN will determine whether it has an X or an O.

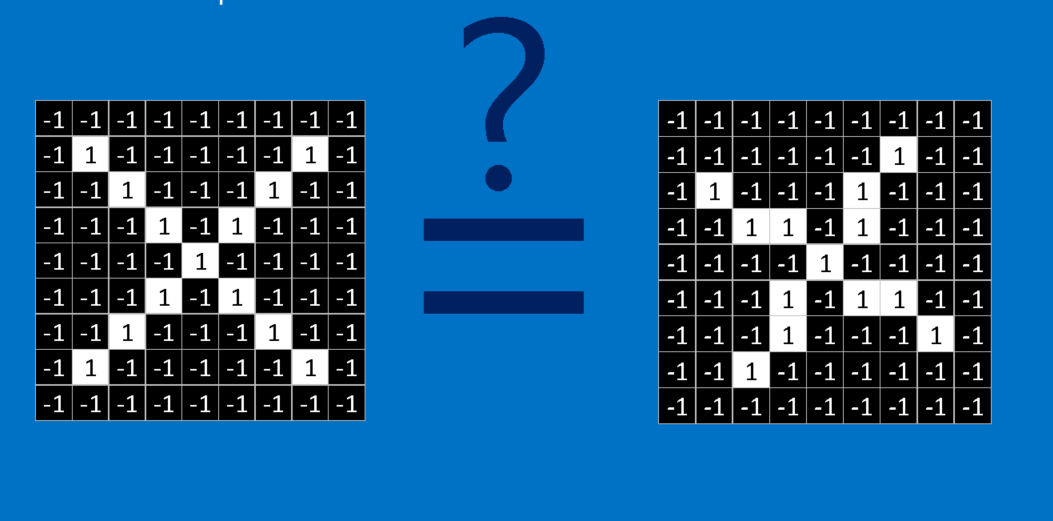

A naive approach to solving this problem is to save an image of an X and an O and compare every new image to our exemplars to see which is the better match. What makes this task tricky is that computers are extremely literal. To a computer, an image looks like a two-dimensional array of pixels (think giant checkerboard) with a number in each position. In our example a pixel value of 1 is white, and -1 is black. When comparing two images, if any pixel values don’t match, then the images don’t match, at least to the computer. Ideally, we would like to be able to see X’s and O’s even if they’re shifted, shrunken, rotated or deformed. This is where CNNs come in.

Features

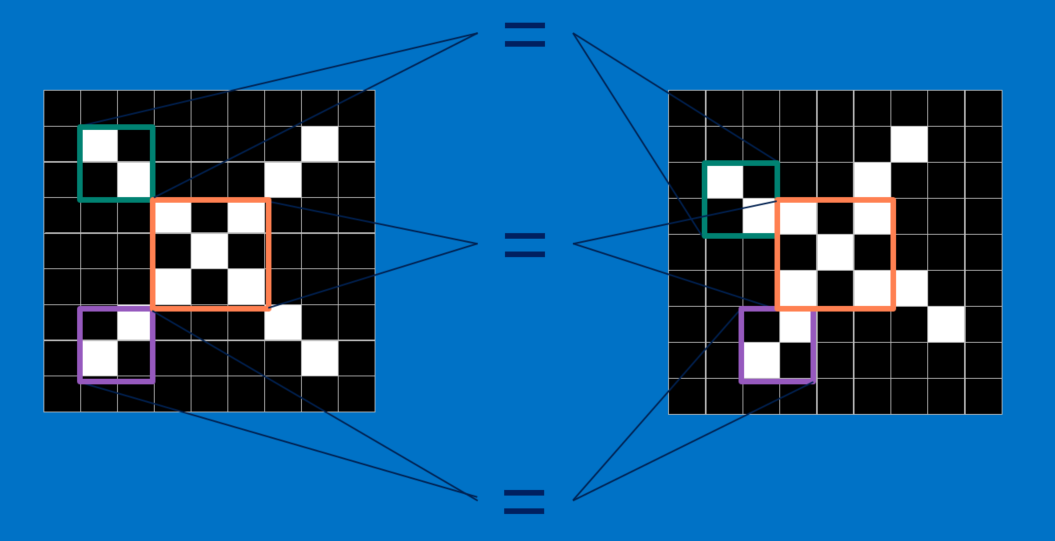

CNNs compare images piece by piece. The pieces that it looks for are called features. By finding rough feature matches in roughly the same positions in two images, CNNs get a lot better at seeing similarity than whole-image matching schemes.

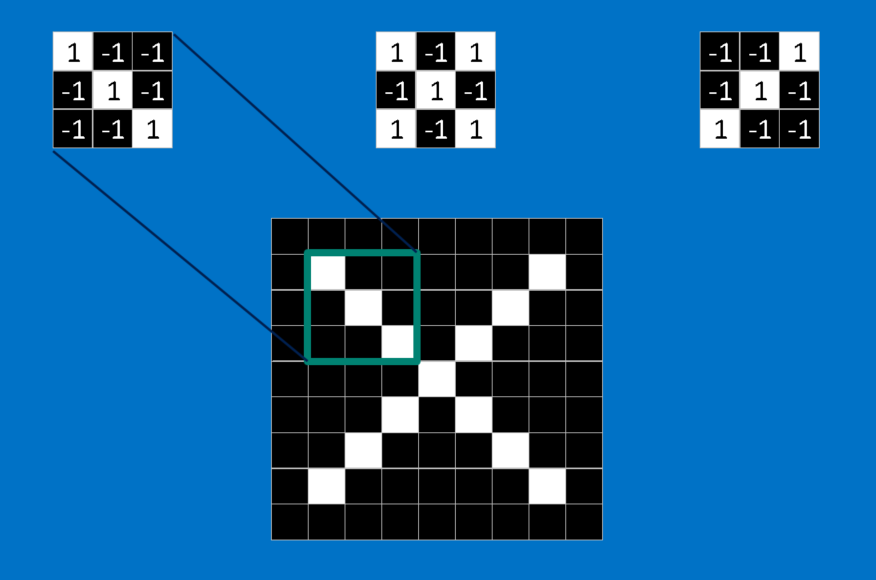

Each feature is a small two dimensional array of values that looks like a mini image. For example, in X image - features consisting of diagonal lines and a crossing capture all the important characteristics of most X’s. Intuitively, these features will match up to the arms and center f image of an X.

Convolution

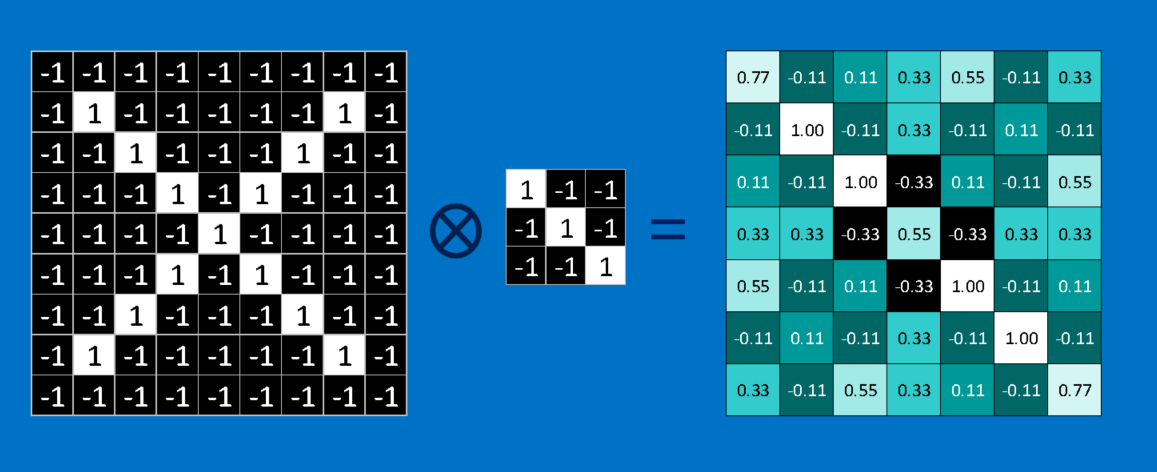

Given an image, CNN doesn’t know where will these features will match up. So to make CNN try to match in every possible place across the whole image, we make a filter. The math we use to do this is called convolution, from which Convolutional Neural Networks take their name. Wolfram have presented this convolution operation in ingenious manner.

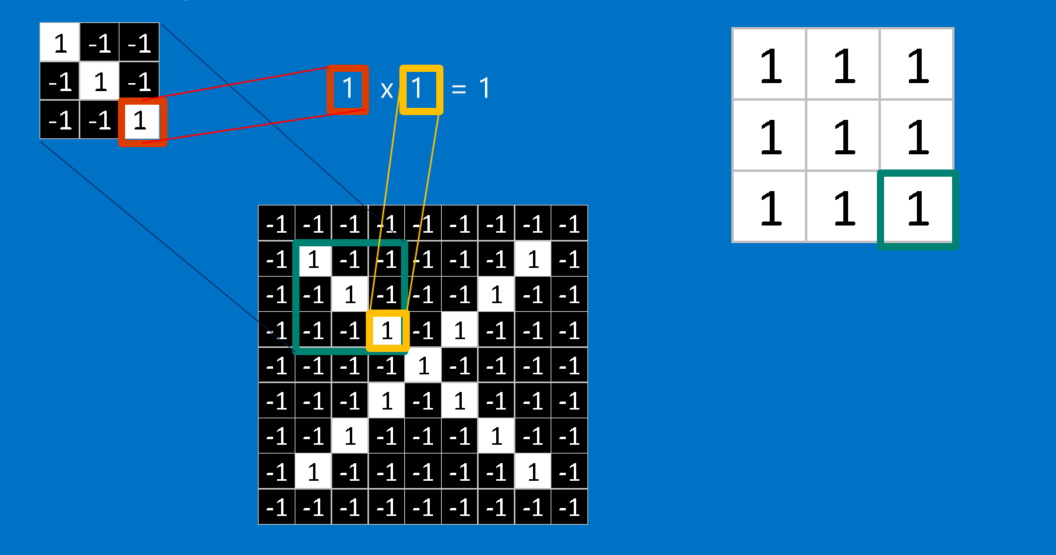

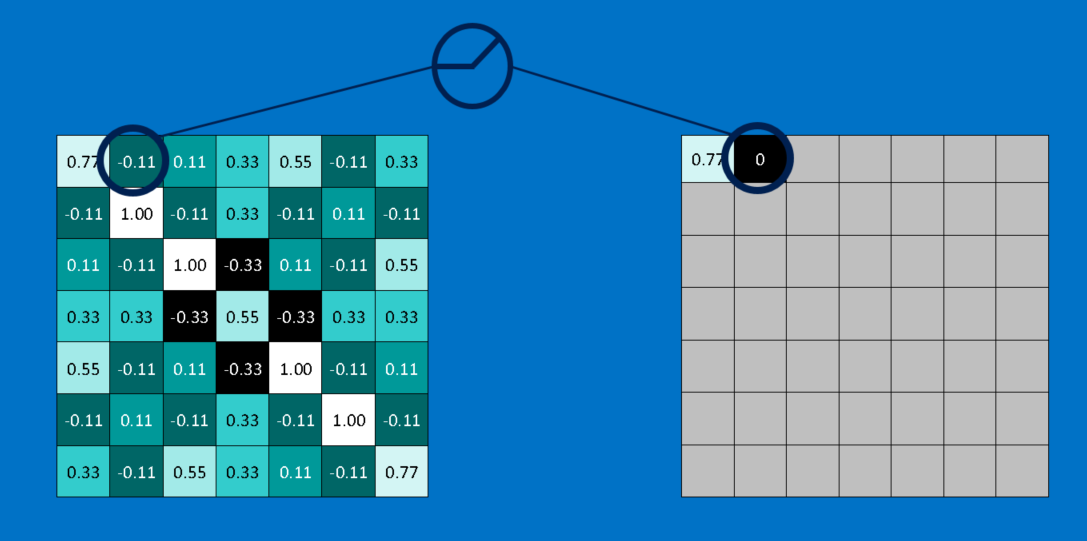

To calculate the match of a feature to a patch of the image, simply multiply each pixel in the feature by the value of the corresponding pixel in the image. Then add up the answers and divide by the total number of pixels in the feature. If both pixels are white (a value of 1) then 1 * 1 = 1. If both are black, then (-1) * (-1) = 1. Either way, every matching pixel results in a 1. Similarly, any mismatch is a -1. If all the pixels in a feature match, then adding them up and dividing by the total number of pixels gives a 1. Similarly, if none of the pixels in a feature match the image patch, then the answer is a -1.

We line up the feature with every possible image patch to repeat the process for completing our convolution. We can take the answer from each convolution and make a new two-dimensional array from it, based on where in the image each patch is located. Its a map that we have created which tells us where in the image the feature is found. Values close to 1 show strong matches, values close to -1 show strong matches for the photographic negative of our feature, and values near zero show no match of any sort.

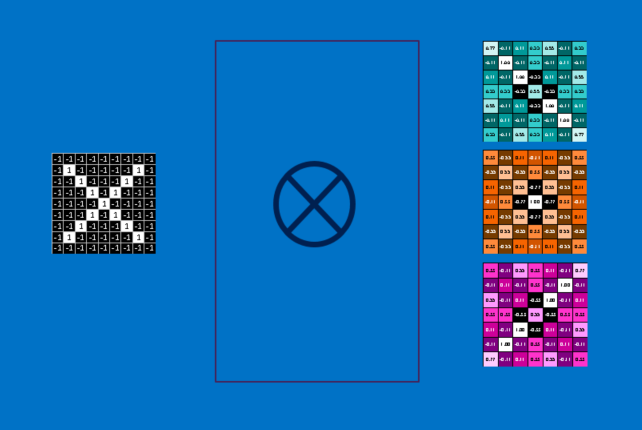

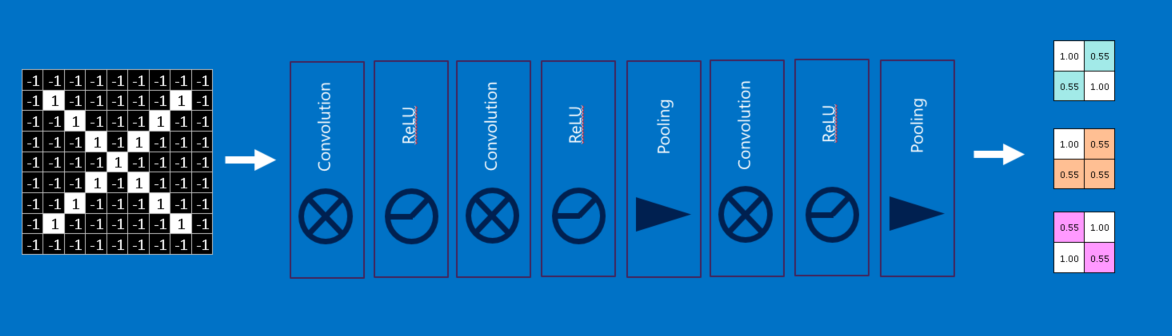

All we have to do now is to repeat the convolution process in its entirety for each of the other features. The result is a set of filtered images corresponding to each of our filters. It’s convenient to think of this whole collection of convolution operations as a single processing step.

Pooling

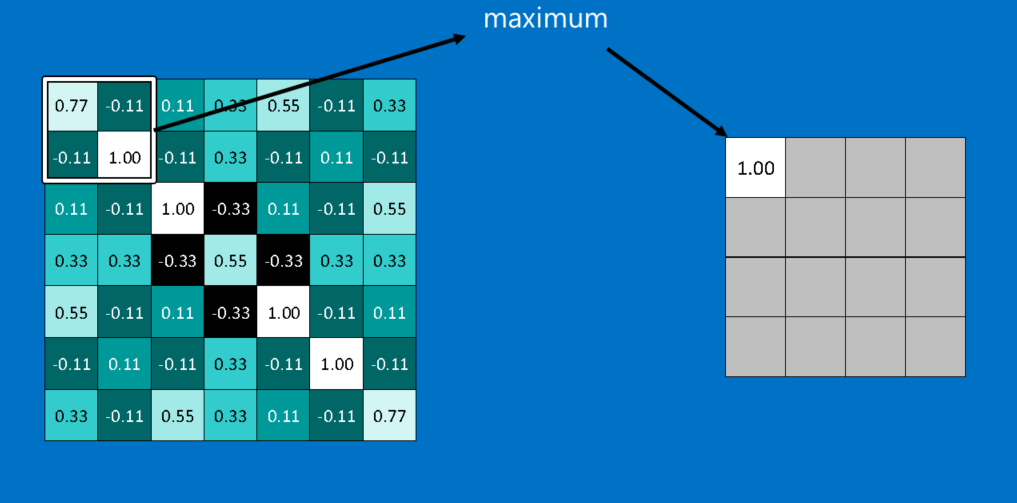

Pooling is an operation of shrinking the image while preserving the most common information in them. It consists of stepping a small window across an image and taking the maximum value from the window at each step. The typical size of windows are 2 or 3 pixels on a side and steps of 2 pixels usually works.

Note that we have created a new image which is about a quarter the size of original image. Because it keeps the maximum value from each window, it preserves the best fits of each feature within the window. This means that it doesn’t care so much exactly where the feature fit as long as it fit somewhere within the window. The result of this is that CNNs can find whether a feature is in an image without worrying about where it is. This helps solve the problem of computers being hyper-literal.

Rectified Linear Units (ReLU)

In this layer we threshold the values obtained from previous layer i.e. we create a lower bound (usually it is 0) for all the entries. This helps the CNN stay mathematically healthy by keeping learned values from getting stuck near 0 or blowing up toward infinity. It’s the axle grease of CNNs - not particularly glamorous, but without it they don’t get very far.

Deep Learning

As you might have anticipated, we are now going to stack all the layers together. Raw images get filtered, rectified and pooled to create a set of shrunken, feature-filtered images. These can be filtered and shrunken again and again. Each time, the features become larger and more complex, and the images become more compact. This lets lower layers represent simple aspects of the image, such as edges and bright spots. Higher layers can represent increasingly sophisticated aspects of the image, such as shapes and patterns.

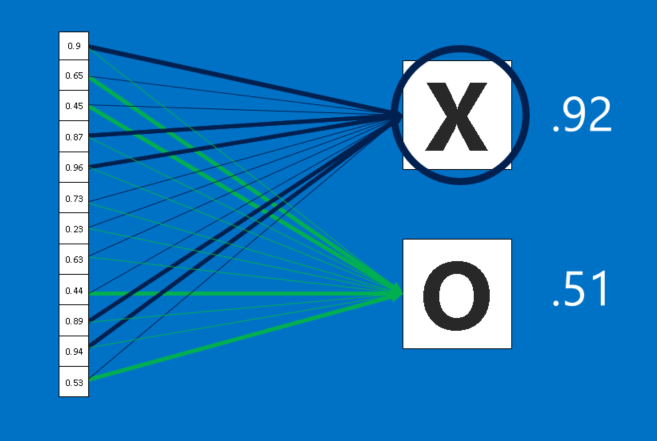

Fully Connected Layers

Fully connected layers take the high-level filtered images and translate them into votes. In our case, we only have to decide between two categories, X and O. Fully connected layers are the primary building block of traditional neural networks. Now instead of using 2D array, we have created a list of values which will vote for each category in the class. The process is however not very democratic as there is a weight associated with each vote that we will train eventually.

When a new image is presented to the CNN, it percolates through the lower layers until it reaches the fully connected layer at the end. Then an election is held. The answer with the most votes wins and is declared the category of the input.

Now these fully connected layers can also be stacked like the rest. In practice, several fully connected layers are often stacked together, with each intermediate layer voting on phantom “hidden” categories. In effect, each additional layer lets the network learn ever more sophisticated combinations of features that help it make better decisions.

Backpropagation

Our story is filling in nicely, but it still has a huge hole—Where do features come from? and How do we find the weights in our fully connected layers?

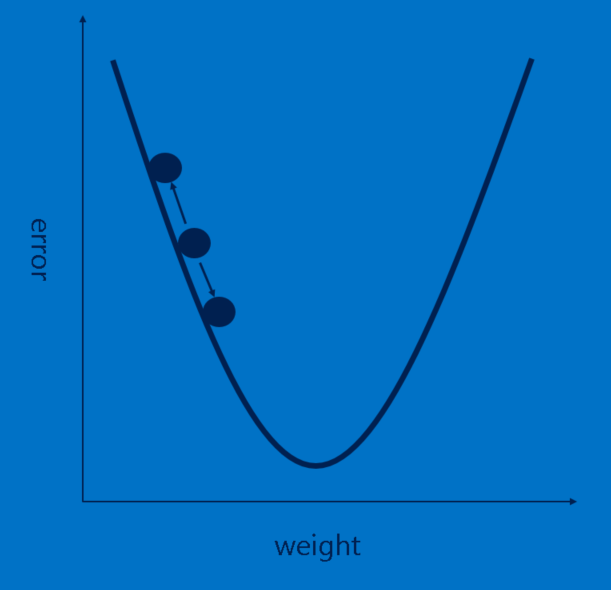

Each image the CNN processes results in a vote. The amount of wrongness in the vote, the error, tells us how good our features and weights are. The features and weights can then be adjusted to make the error less. Each value is adjusted a little higher and a little lower, and the new error computed each time. Whichever adjustment makes the error less is kept. After doing this for every feature pixel in every convolutional layer and every weight in every fully connected layer, the new weights give an answer that works slightly better for that image. This is then repeated with each subsequent image in the set of labeled images. Quirks that occur in a single image are quickly forgotten, but patterns that occur in lots of images get baked into the features and connection weights. If you have enough labeled images, these values stabilize to a set that works pretty well across a wide variety of cases.

Hyperparameters

There are some parameters that a CNN designer must choose before setting it to learn. Here are some of the parameters :

-

For each convolution layer, How many features? How many pixels in each feature?

- For each pooling layer, What window size? What stride?

- For each extra fully connected layer, How many hidden neurons?

- Additional architectural decisions:

- How many of each layer to include?

- In what order?

With so many combinations and permutations, only a small fraction of the possible CNN configurations have been tested.

Sources

- Brandon’s Blog

- Convolution

- University of Illinois at Urbana Champaign - CS 446

- Stanford University (CS231 notes)

Feel free to reach out to us, and of course keep an eye on our blog. Comments, corrections and feedback are welcome.